The show is called “Fat Phobia” and is part of a larger multi-faceted program called “The Body Image Project.” Those at Art Access, which is a community-focused organization that uses art to drive ideas, wanted to tackle the concept of personal and social body image perspectives by deepening the conversation of weight. Within The Body Image Project was the Fat Phobia exhibit.

“I remember telling someone, ‘Oh, I was invited to do the Fat Phobia show.’ And someone said, ‘They’re calling it that?’ And I thought, you now, really, just the word ‘fat.’ ‘You’re going to use that? You’re going to put it in print? Like, aren’t you going to offend somebody?’ I mean, it is so ingrained in us that it’s, like, a bad word,” said Zoë Rodriguez, a photographer who contributed a series of photographs to Fat Phobia.

The purpose of The Body Image Project, and pushed visually with the Fat Phobia exhibit, is said perfectly with a statement by Salt Lake City artist Phoebe Berrey:

"Going out in the world as a fat woman is a constant balancing act because you are exposed, and there is no net between you and the abyss. You are just a “fat girl” to most of the people who see you, no matter how many Spanx, hair weaves, mani-pedis, or great clothes you have. You are probably a fat girl to yourself, too. And because of your appearance, you are judged to be less intelligent, less ambitious, less sexy, less worthy of a decent job or a fair salary, and less desirable as a friend. So every morning you get naked on your tightrope. You try to make it through the day without crashing and burning. And you try not to hate yourself for failing to be “normal.”

Through different forms of art, a group of artists expressed their thoughts and feelings about this topic. Here’s Carol Berrey, co-curate of the exhibit, to explain her piece called “Tightrope.”

"This painting is about three feet by three feet," said Carol, as she described her piece Tightrope. "It shows an obese woman in a ballet pose on a tightrope. The rope is suspended over an abyss, and there are dark clouds above her, but she’s illuminated by light. [She] has her arms out and she’s totally in control of things.

"In my family we’ve always been obese and we’ve always struggled with how you deal with it and how to be in the world when you’re fat or when you’re not and how people treat you. I felt like our life was always a balancing act, and that if you got off the diet or if you stopped fighting being fat, you’d fall into the abyss - even though you are a very competent person and you have something to offer the world, the world doesn’t always see that."

Photographer Zoë Rodriguez’s piece is a straight-on, close-up, black-and-white photograph of an obese woman’s midsection. The model she used was named Amanda and Zoë used her to explore the idea of that it’s like to be big in this world.

"I really wanted to know her story," Zoë said. "'What’s your perspective? What do you feel, what do you see, what is your experience in this everyday world of skinny and should?' So, we got to the studio and just started taking off her clothes and eventually these shapes and shadows and lines came out that were just so beautiful."

For Zoë, it became more than creating a beautiful piece of art – with this experience, with this model - she actually broadened her view of beauty in the world and in herself.

"I’d love to see us all do that - look at a body and see the beauty without having all of this other stuff behind us, telling us what we should and shouldn’t like."

Sculpture Jonna Ramey created 2 stone works of art that are similar to the prehistoric piece “Venus of Willendorf.” It’s a small, nude statuette of an obese, faceless woman made sometime between 28,000 to 25,000 BCE.

"And she is so beautiful and so luscious, and so unabashedly fat," Jonna said. "And I always wanted to do my own take on that. So when this project came up, I proposed the idea of creating two sculptures. One, 'Venus at Middle Age,' which is my take on that specific sculpture from 28,000 years ago, but instead of her being a young woman, I middle-aged her. So her breasts sag a little bit, her rear sags a little bit, but she’s stronger, she’s had more life. Then the other sculpture I did is called 'V kicks up her heels' and the idea of that piece was to do a contemporary take on fat women, and I wanted it to be more playful, I wanted it to have a life, that I think actually, I saw was reflected in Carol’s painting of the woman on the tightrope. That this is a woman in control of her life in this world today."

Jonna wanted to create these pieces in celebration of the natural woman, as she says, at any age and size.

Artist Terrece Beesley, took a more tongue-and-cheek approach to the exhibit's theme. She took the idea of the unrealistic expectations that are often put on women one step further.

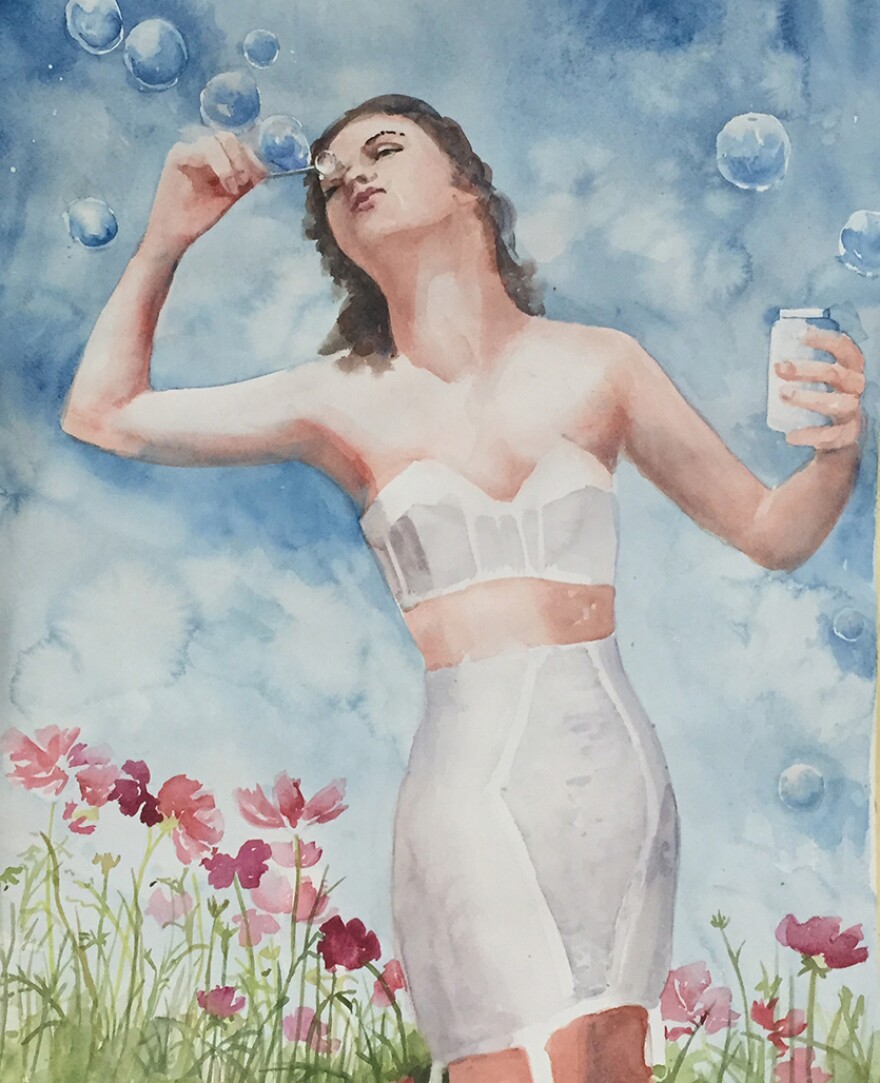

"When I approached this show," Terrece said, "I was interested in what society teaches us to do with our bodies. For instance, in the Middle Ages a heavy woman was attractive because heavy meant you could afford to eat. Then we move onto the Victorian Age and suddenly we had to have 12-inch waists. Women were actually breaking their ribs to fit into these corsets. We move into the flapper era, everyone has to be flat-chested. Then my favorite, my personal favorite, the Fifties, when women started wearing those awful steel-framed girdles. So when I was approaching this, I found an advertisement for a girdle. It had a woman, standing in the middle of the room, blowing bubbles because obviously that’s what we would do. So I thought, 'How can I take this ridiculous image and make it even more so?' And my answer was to take this woman and put her in a field of flowers, blowing bubbles. Because, again, that’s what we would do in that girdle."

Terese said that women have lived through the girdle age, but present day, the garment is making a comeback but is just called something different.

"But now we’re back, we’re all wearing Spanx. Well, I’m not, but a lot of people are. And it’s just an updated girdle. So we haven’t really learned much. We are still trying to have great big boobs and twelve-year-old hips."

Each artist brought her own ideas to the Fat Phobia exhibit, but after I spoke to most of them, they all agreed that they wish women and men alike would aim to be healthy instead of trying to fit into a physical mold.

There’s an organization run by two sisters out of Salt Lake City called Beauty Redefined, which tries to combat this idea that there’s a mold we need to fit.

In a recent Instagram post, those at Beauty Redefined said that the beauty industry is worth more than $100 billion and shockingly does not drop with a weak economy. Similarly, diet and weight loss industries make about $70 billion each year, and these sisters say almost no one is successful at losing weight and keeping it off in these programs. Plastic surgery has more than doubled in the last decade, with 92% of the procedures performed on girls and women.

Those involved in Fat Phobia wanted to create art to inspire the kind of change that will promote, rather than destroy, health and well-being.

"The reality is that there are so many different body types on the planet and we celebrate in our culture a very narrow body type," said Johnna. "I think if we can always work at expanding the range of what is seen as beautiful and what is accepted in our culture, we all benefit from that. Because, if you look at all those little kids just coming into puberty, little boys and girls, and you say to all of them - short, tall, fat, thin, whatever - that ‘You’re good, you’re good” and let’s go from there. It just rocks. It makes everything so much better."

***This segment is part of an ongoing original Utah Public Radio series "Objectified: More Than A Body." Support for the program comes from the Utah Women's Giving Circle, a grassroots community with everyday philanthropists raising the questions and raising the funds to empower Utah women and girls. Information here. To learn more about the Objectified radio series, visit here.