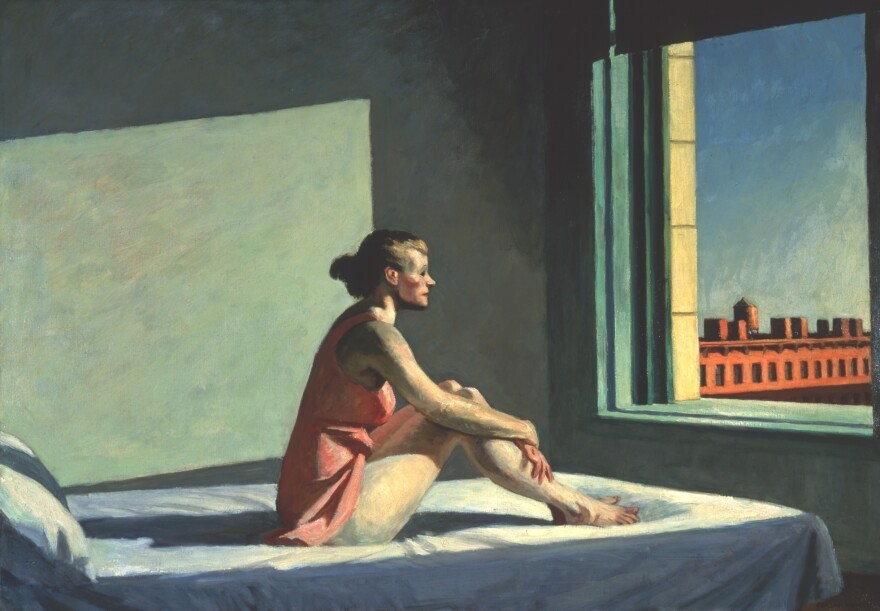

Earlier this summer, I looked for Edward Hopper's Morning Sun at its home in the Columbus Museum of Art in Ohio. In the painting, a woman sits on a bed with her knees up, gazing out a window. She's bare, but for a short pink slip. The iconic Hopper is a must-see, but on the day I visited, it was on loan to an exhibition in Madrid.

I finally caught up with Morning Sun in Paris, where it is on display as part of a Hopper show at the Grand Palais. When I first walked in, the gallery was empty, but not for long. The room quickly filled — as has the whole exhibition — since it opened in October.

Curator Didier Ottinger says the crowds for the Hopper show rival the crowds for Picasso or Monet exhibits — and that surprised him. He never expected his exhibition of the American realist's work to become such a phenomenon. Though Hopper is a favorite in the U.S., French museums don't own his work, so the French don't know the painter very well. Now that they've been introduced, they like him quite a bit — they like his colors, his people and his light.

Hopper shows men and women, bathed in light from open windows, or under fluorescent light — those figures drinking coffee from hell in a nighttime diner. They all seem isolated and lonely. The fact that the images are based on the lives of ordinary people is very American, Ottinger says, but the French still see themselves in these paintings. "Each of his works is a kind of screen where everybody ... is able to project his own feelings, his own emotions," Ottinger says.

Hopper never painted narratives; it's up to us to impose our own stories on his images. But, says Ottinger, there are autobiographical elements in the paintings. In Hopper's 1932 painting Room in New York, a man and a woman sit together but alone. The man is engrossed in his newspaper; the woman seems lost in thought, one finger placed on the key of a piano. They're so removed from one another.

"And this is precisely the time when his wife, Josephine, was starting to write her own diary where she expressed her frustration because he was becoming a famous painter," Ottinger says.

Edward and Josephine Hopper met as young students in art school in New York and married in 1924. "And very, very fast he became one of the key figures in realism of this period, and she was left behind," Ottinger says.

At her insistence, she became his only model. That way, Jo felt that she played a part in the creation of his paintings, and Hopper encouraged this interpretation. Jo had wanted to be an actress, but that never worked out, Ottinger explains, so her husband "gave her this kind of chance to be his only actress, and every single painting is a kind of small play."

So that's Jo in the pink slip, sitting by the open window in Morning Sun. "More than solitude, more than melancholy, this painting is expressing a kind of awakeness," Ottinger says. The woman staring out that window is aware of what the day and her life are really about.

"She's awake ... ," Ottinger says, snapping his fingers. "There is something higher, there is something bigger, there is something more cosmic than this sad and ordinary life which is expressed by this gloomy room. ... I think this is precisely what is always interesting — something which can be depressing, but at the same time, there is always hope."

Edward Hopper, seen in a new light in Paris. (A friend says Hopper — himself a Francophile — would be thrilled to find his works on view so near the Louvre.) Ottinger's exposition of this major 20th-century American painter remains at the Grand Palais until the end of January.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.