The Shanghai Propaganda Poster Art Center lies buried in an unmarked apartment building off the tree-lined streets of the city's former French Concession. There are no signs. You have to wend your way through apartment blocks, down a staircase and into a basement to discover one of Shanghai's most obscure and remarkable museums.

The private collection features about 300 brightly colored, Mao-era propaganda posters stretching from the founding of Communist China in 1949 to 1990, which includes some of China's darkest political days. The museum, which has been open for a number of years but finally received an official government license last spring, is a labor of love.

Its owner, Yang Peiming, began buying up the posters in the mid-1990s as they were being thrown away en masse.

"The propaganda poster is very, very unique," says Yang. "They describe the history with so many detailed pictures. This is interesting, because it is art plus politics."

Many posters feature heroic, cartoonlike figures with political slogans to rally the masses. The images are triumphant, even if the events they depict were often disasters.

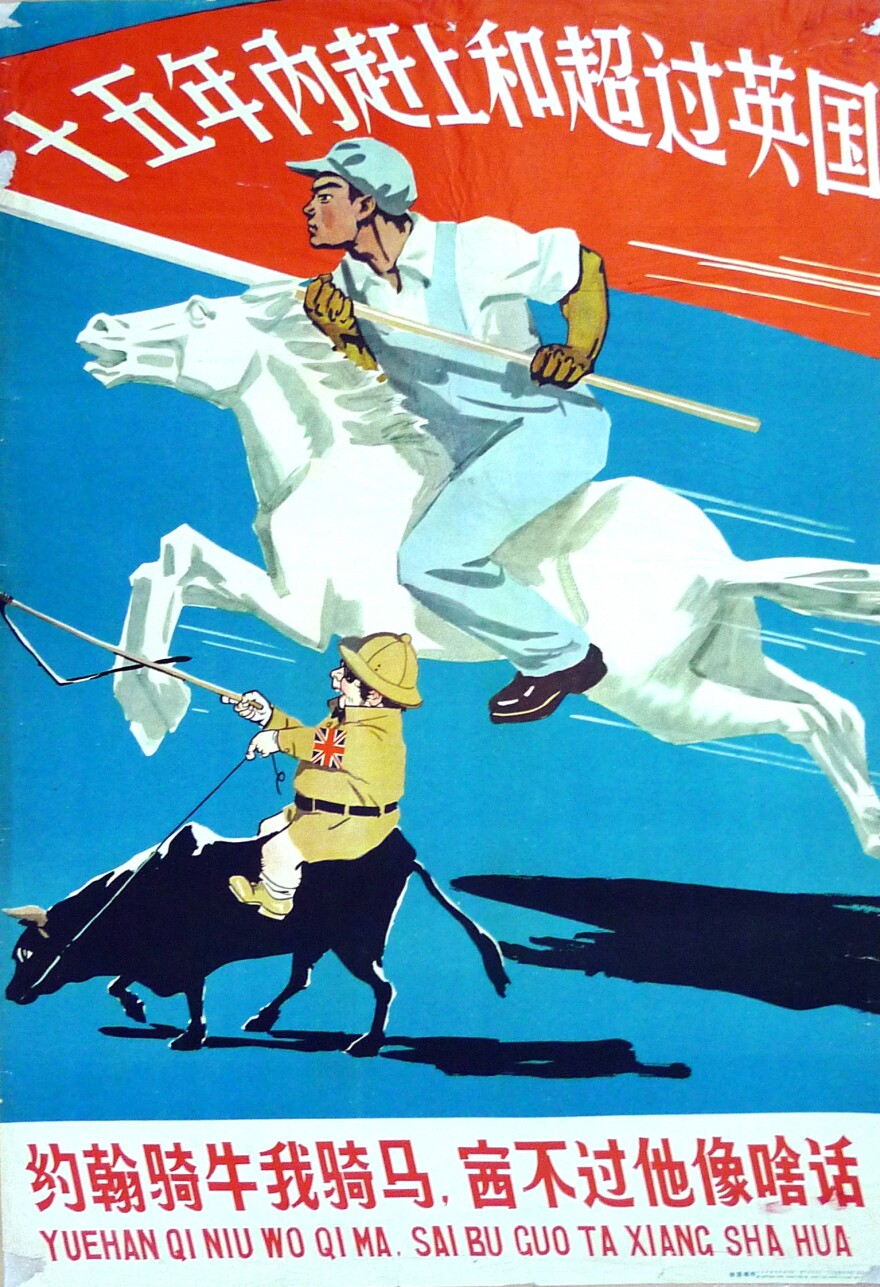

Take a poster from 1958 showing a Chinese man on horseback racing past a portly British soldier in a pith helmet on the back of an ox. One of the poster's slogans says China's economy will surpass Great Britain's in 15 years. The poster was a rallying cry for Mao's Great Leap Forward, which forcibly collectivized agriculture.

It was a catastrophe that that Yang calls "crazy."

"We got a famine disaster and people [didn't get] enough to eat," says Yang.

At least 30 million people died in the resulting famine.

Yang says the posters help Chinese appreciate the country's recent boom years by recalling the mistakes and suffering of the past. "If we want to taste the sweetness, you have to know what is the taste of the bitterness," he says, using an old Chinese slogan.

Because the museum is not well-known — most Shanghainese have no idea it exists — it doesn't attract crowds.

"It's a hidden treasure," says Ruby Leung, who grew up in Hong Kong and visited one recent weekday.

Leung's favorite works are a series of nearly identical posters first dating to 1953. They show Mao standing atop Tiananmen, Beijing's main imperial gate, announcing the creation of the People's Republic of China, flanked by fellow party leaders.

What fascinates Leung is how officials in the background vanish with each new rendering. It's the political equivalent of the children's song "Ten Little Indians."

Yang explains the first figure to disappear is a senior party official named Gao Gang.

"He was sold out by Stalin," Yang explains to Leung. "Stalin told Mao that your Gao Gang wants to replace you, so that made Mao very angry."

Gao was purged and committed suicide in 1954.

Next to go was Liu Shaoqi, China's president. He was labeled a traitor in the late 1960s and died in prison.

"So, Liu Shaoqi disappears in the third edition replaced by another man," says Yang, who likes to explain the posters' historical context to visitors.

Leung, who now works for Citigroup in New York, says her mother was sent to work in the countryside during the Cultural Revolution, when Mao turned Chinese society on its head.

So the posters have a personal resonance. "It is a good opportunity for me to understand more about my country," she says.

Frank Langfitt is NPR's Shanghai correspondent.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.